Shahana Rajani explores the work of three printmakers from Thailand who use a vocabulary emanating from a mix of their rich cultural heritage and from universal ideas.

Believer’s Paradise’ features the works of three international artists from Thailand exhibited at Koel Gallery in August, 2011. Curated by Syed Faraz Ali, the exhibition provides the Karachi audience with the rare chance to view contemporary Thai artistic practices firsthand, especially in regards to printmaking. The show begins with the works of Panuwat Sitheechoke. His monochrome prints emit a palpably morbid aura. His etchings titled ‘Human’ show child-like figures aligned in rows. While their bodies are drawn in simplistic outlines, the faces are etched in a dark charcoal texture with their facial details intentionally scratched out, giving them a haunted and ghostly appearance.

Another etching, titled ‘Recticulur’ shows human bodies lying horizontally, some limp, some struggling. The artist explains using ‘reticulum’ – a netlike structure – as a symbol for human ambition and struggle. This patterned reticulum runs over the contours of his human bodies, like a wire-mesh digging into the human flesh. The artist finds dark inspiration in his realization that human existence is always weighed down by societal pressures. He portrays the human psyche as forever cursed and inherently malignant. The scratching out of facial features represents the loss of individuality which results from our desire to conform to society.

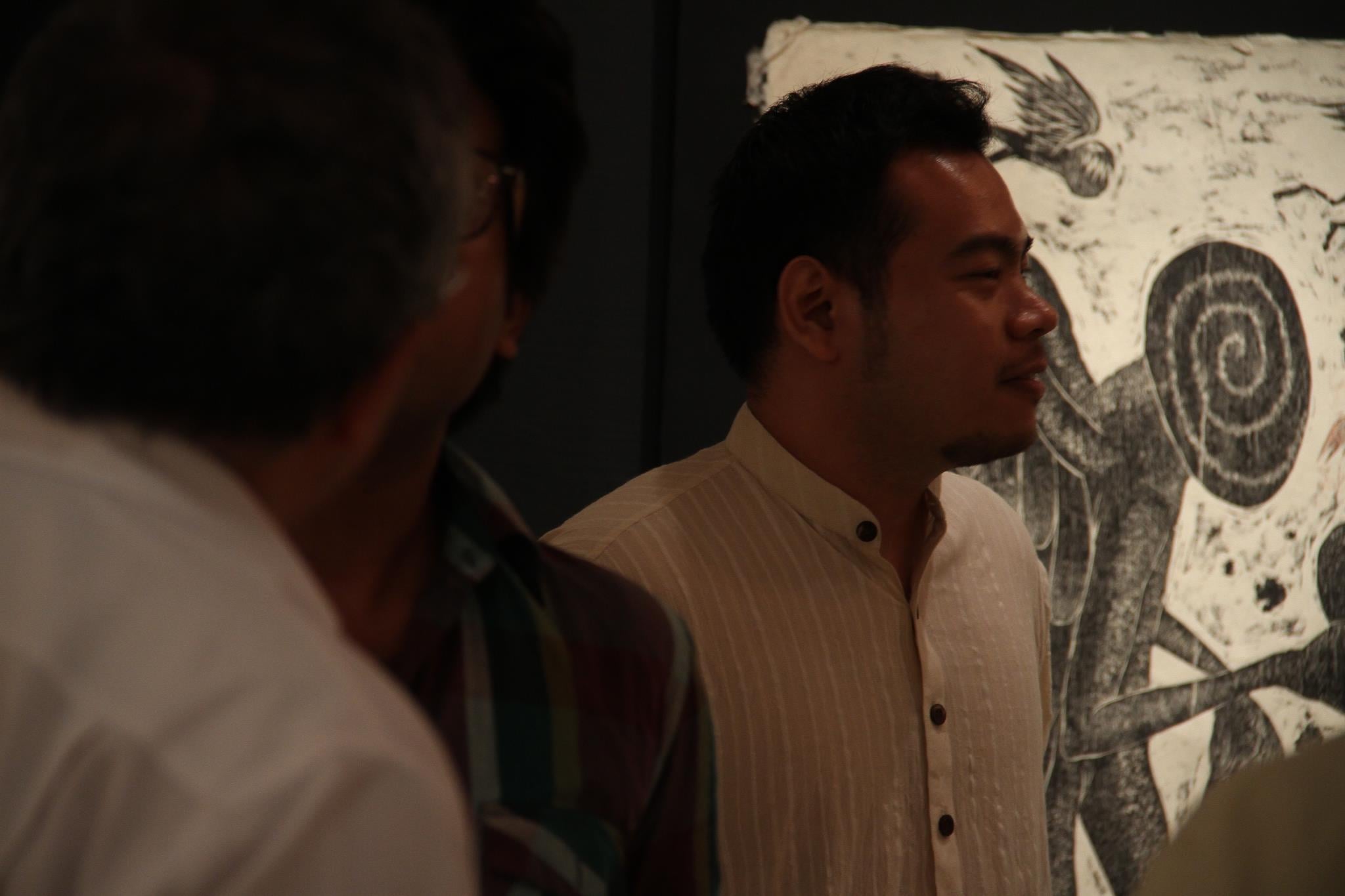

Kriangkrai Kongkhanun has on display a series of large woodcut prints, titled ‘Spiritual Disease’. The phantasmagorical creatures – which include animals, humans and plants morphing into one another – are reminiscent of demons and hell. For example ‘Touching of Ignorance’ shows a well-dressed person morphing into a four-headed monster, surrounded by primeval winged creatures.

The imagery of such surreal creatures is common in the Buddhist popular culture of storytelling, myths and fables, as well as in Buddhist art found on temple murals. The iconography derives from the fourteenth century Thai text Traibhumikatha (“Three Worlds According to King Ruang”) which describes Buddhist cosmology and the different realms of hell. The woodcuts also have a strong resonance to the works of Hieronymus Bosch, a fifteenth century Dutch painter, famous for his use of fantastic and strange imagery to illustrate religious and moral concepts. While Bosch was an illusionistic painter, Kongkhanum translates such imagery into prints in an equally graphic and compelling manner.

The artist explains that his chimeras symbolize base human instincts and wicked desires, which when once surface, ‘germinate every particle of the spirit’. He claims to be acutely aware that the negative human traits typified as ‘evil’ are so deeply woven into the subconscious, that they are an undeniable part of human existence. His illustrations are meant to convey the darkness and chaos of evil. The technical expertise of his works engrosses the viewer, transporting them to the artist’s realm of fantasy and horror.

The third artist, Arthit Amornchorn, deals with lighter subject matter saving the exhibition from becoming excessively dark and dreary. While the previous two participating artists worked in monochrome, Amornchorn’s prints stand out in splashes of colour. He takes ordinary everyday objects, combining their different parts to form bizarre, nonsensical objects which hold a child-like appeal.

The artist concocts these objects by recalling his childhood memories and experiences because that was a time when objects were not valued for their utilitarian benefits or economic worth, but simply for their marvelous appeal to the child’s imagination. He explains that every object in his work represents the curiosity and satisfaction that he experienced from possessing those objects as a child; when things as simple as sticks and leaves presented him with millions of fantastical possibilities.

All three artists explore themes with a universal appeal, stepping away from geographical socio-political issues, to more essential concerns about human existence. With limited influx of international art in Pakistan, the exhibition encourages a global dialogue between the art communities of the two respective countries, and will hopefully set precedent for an increase in showings of international artists in Karachi.