Despite major differences between Christianity and Buddhist ethics, their perception of the world and philosophy of life, obvious parallels also exist. Both religions point the way towards deliverance from selfishness, spiritual blindness and from succumbing to worldly desires. In both cases, religious experience and inner transformation offer a practical path to salvation. Not only intrinsic moral values but also an all-embracing call for goodness, joy, compassion and love are mutual fundamental traits. The yearning for discipline, justice, morality and an ethical conduct in Buddhist teachings is likewise a fundamental component of Christian thought. The image of evil is also similar. Both religions recognise demons and Hell where, after death, sinners are mercilessly tormented by the inhabitants of the Underworld for their shortcomings on Earth.

One of the greatest masterpieces of traditional Thai literature, King Lithai’s Traibhumikatha (The Three Worlds), written in the mid 14th century, describes the three different realms of Hell in the First World where the torment to which sinners are subjected serves to purify them and rid them of their shortcomings. In Buddhism, salvation comes ultimately to everyone whereas in Christianity, the fires of Hell burn for all eternity. Thai Buddhists are generally familiar with the imagery in Traibhumikatha from temple murals. Even today, young artists studying traditional Thai painting at art colleges still draw on the imagery found in ancient Buddhist art and its myths, fables and tales, weaving it into a highly decorative and narrative fabric of people, animals and unknown creatures which are equally fascinating to a foreigner’s eyes.

In contemporary western art, pictures of demons, fantastic creatures, Hell and the Underworld are seldom to be found. Paintings of the Late Gothic period and the Renaissance immediately spring to the minds of those familiar with European art, however – Mathias Gruenewald, Pieter Brueghel the Elder and his son, the ‘Hell Brueghel’ – as well as Symbolist painting in the second half of the 19th century, Gustave Doré’s illustrations for Dante’s Divine Comedy and Milton’s Paradise Lost, or Moreau, Redon, Böcklin and Klinger. Today, monsters and demons and the fantastic worlds they populate are largely to be found in the world of the comic and animation film.

Kriangkrai Kongkhanun, who studied at art schools in Thailand as well as in Italy, visiting the most important art museums in the West on a trip to Europe, makes a daring attempt to forge a link between the Buddhist symbolism found in traditional pictures and the western imagery of the Renaissance and the 19th century. The Buddhist codex of ethics conditions his life philosophy and way of thinking. The point of departure for Kriangkrai’s art is, however, the knowledge that negative human traits, such as anger, hatred and selfishness, namely evil properties, are so closely woven into human life that they always resurface from the subconscious.

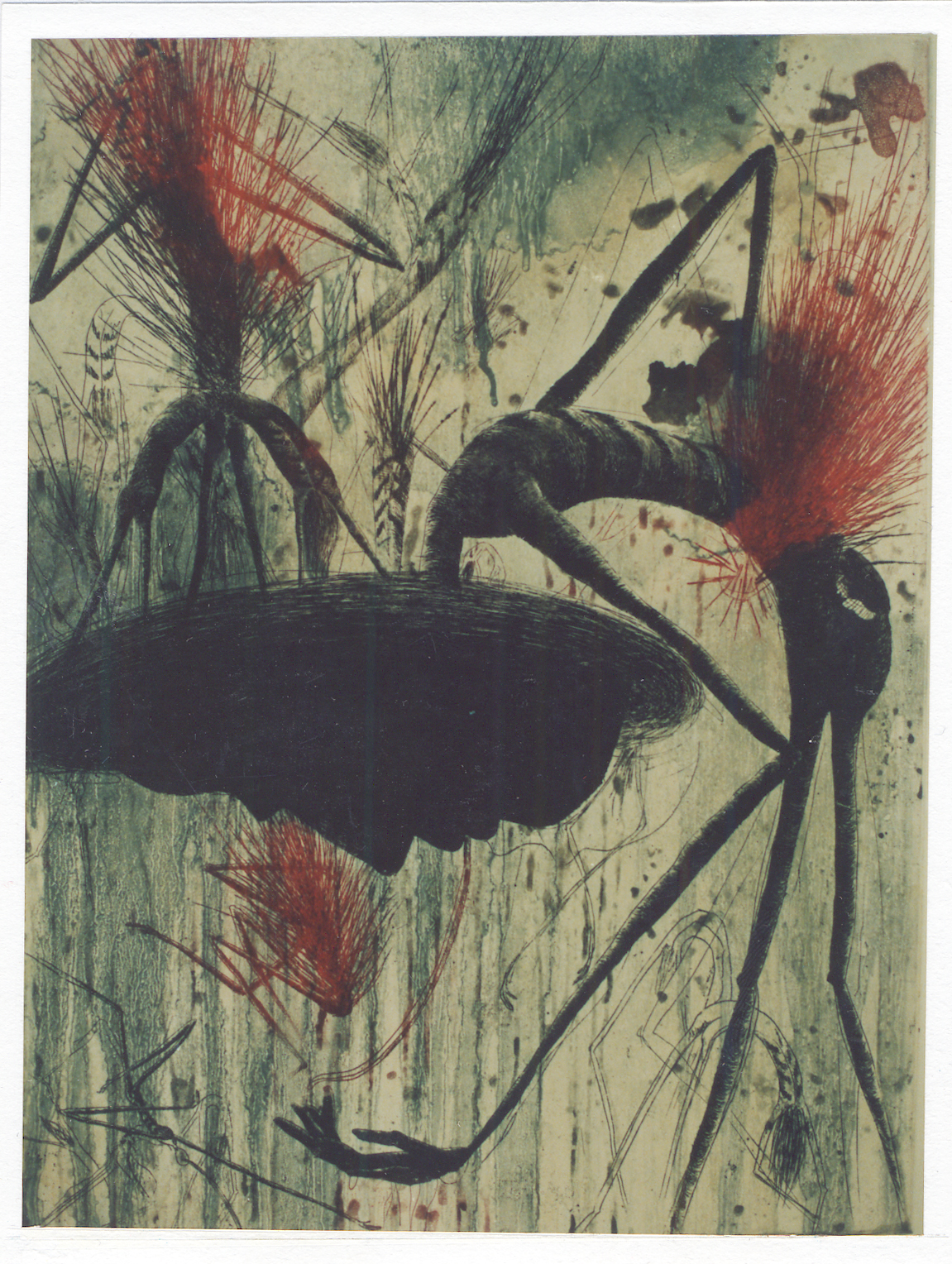

Images of evil concealed within the subconscious form the predominant theme in Kriangkrai’s art. In etchings made in 2001, images of the smallest of primeval creatures and amorphous coloured forms and shapes mutated into images of demons. Insect-like creatures filled his imaginary world of Purgatory. The following year, he switched to woodcuts as this technique gave him greater possibilities for expression for his depiction of creatures from the realm of shadows. They should give the viewer an idea of what awaits sinners in Hell. Ancient illustrations for Traibhumikatha, the book of Heaven and Hell, and the pictorial symbolism of Buddhist mural painting provided the inspiration for Kriangkrai’s interpretation of evil and Hell. In European art history, depictions of the temptation of St. Anthony and his being tormented by the Devil and demons by Hieronymus Bosch (c. 1505/10) and Matthias Gruenewald (c. 1515), for example, are close to Kriangkrai’s world of thought. Gustave Doré’s steel engraving for Inferno of 1861, to illustrate Dante Alighieri’s journey in the Divine Comedy through Hell in the afterlife, drew the artist into a close pictorial relation with his own vision of Hell as understood in Buddhism.

Kriangkrai’s series of woodcuts ‘Touching of An Ignorance’ of 2009 once again refers to the eternal desires that arise out of the subconscious and that mankind cannot resist despite his striving for good. From a correctly dressed individual in a suit and tie, they develop into a four-headed monster with countless eyes and faces, holding the mask of evil up to the winged chimera. In the series ‘Spiritual Disease’ four related pictures in each case with different winged demons, insects with human heads, fantastic reptiles, carnivorous plants with snarling jaws and wondrous flowers and vegetation represent the scourge of the soul. The demons of the Underworld are not shown as realistically imaginable creatures but as the embodiment of evil. They are Hell on earth.

Despite all art-historical references, Kriangkrai’s imagery has a considerable strength of its own and reflects an unmistakable personal style. The little details, figures and structures cut into the wood are just as precisely executed as the larger shapes that dictate a picture’s overall composition. The interspersion of black and white, structured, monochromatic fields heightens the element of suspense, the pictorial surface being designed as a dramatically composed ornamental form comprising fascinating individual shapes. For this series of works the artist won a major award at the 55th National Art Exhibition in Bangkok and succeeded in beguiling not only experts in Thailand itself but western critics as well. Since 2003 his works have been shown at numerous exhibitions of graphic works in Europe and in South America, as well as in Japan and China.

The technique of pulling prints after rubbing the cut and inked woodblocks himself, enables the artist to remain in close contact with his materials. Other than in the case of most European artists who use heavy woodblocks and presses when printing, Kriangkrai works on large-format, thin wood veneers. He employs a technique similar to frottage, rubbing over the grain of wood and the surface structures of other natural materials. Max Ernst – the Master of Surrealism – saw such shapes as new and unknown worlds rising from the subconscious. And if we look at the pictorial elements favoured by the Surrealists and at Max Ernst’s invention of creatures from an unreal universe, then it is not far from there to Kriangkrai’s working methods and imagery. His woodcuts are a new and important contribution to the genre of fantasy painting.

Dr. Axel Feuss

(Curator, Freelance Writer and Guest Lecturer in Art History at Silpakorn University.)